Introduction

In this tutorial I will walk through the code used for a basic model that I used to scrape through the traffic citations database stored on the BYU server.

(Though the example is particularly directed towards BYU students, the structure and syntax of the example can be applied anywhere)

All code in this tutorial is posted on my Github here.

Through my experiences of trial and error and much headache of not being able to figure out why my code isn’t working, and by watching countless tutorials myself, I want to make this tutorial to demonstrate the best way I found to go about scraping data. Though there is never one correct way to solve a problem, I believe there are more efficient ways. In this tutorial I will demonstrate the pitfalls to avoid and the reasons I have structured my code the way I have.

Setting up Selenium

This tutorial assumes that you are generally comfortable with coding and running Python programs. I won’t go explicitily into the details of setting up the Selenium driver (that’s not necessarily the purpose of this tutorial), as there are couple different ways. If you have trouble setting up your driver, I recommend watching this tutorial.

I will be using Chrome and the Chrome webdriver for this example, though any differences are neglible if you use Firefox.

The Selenium webdriver relies on an external program to automate its processes. This acts as the “user.” Through this webdriver (which is essentially a browser that we can send commands to through Python), we will be able to send requests to the server and interact with the HTML elements.

Here’s the general process of how to set up the Selenium driver:

-

Download/extract the driver that is compatible with your browser. If you are using Chrome, you can download the ChromeDrivers here.

-

Install and load in the following python modules in your code:

#import selenium libraries

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait

from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

- In your code, initialize the driver:

PATH = "Driver\chromedriver.exe"

def selenium_driver():

service = Service(PATH)

options = Options()

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=service, options=options)

return driver

NOTE: The most recent version of Selenium requires you to pass in a Service() object just as I defined above. Before you could have just passed in the PATH to your driver.

Right now I am using the default options, but the options can be configured to always open up in a certain way: i.e. in a certain language or in a certain sized window.

If this is the python file that you are running (either directly or from the terminal), we can initialize the driver object when the program is run:

#Create the chrome driver that can be referred to globally

driver = None

if __name__ == "__main__":

driver = selenium_driver()

It is important that you declare the driver variable outisde of your methods so it can be referred to any instance or method.

NOTE: Alternatively, if you cannot find a compatible chromedriver that matches with your version of Chrome, Selenium built a module that will install and do that for you:

from webdriver_manager.chrome import ChromeDriverManager

#Alternative to installing a driver manually

def selenium_driver():

service = Service(ChromeDriverManager().install())

options = Options()

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=service), options=options)

return driver

This can be a little bit finicky though if not all the permissions to install and delete files are met by the python file inside certain folders in your hard drive.

If Selenium is installed and your chromedriver is set up correctly, with the code above typed up in main.py for example, running python main.py in the terminal will store a webdriver instance to our globally declared driver variable. We will use this driver object throughout the scraper process. This will be the object that is uniquely responsible for interacting directly with the chromedriver and our code.

Nothing will really happen when you run this code because we haven’t asked our driver or code to do anything. Let’s change that.

The Problem: Defining the Parameters

In this applied example I will be demonstrating how to set up a scraper that will reliably scrape the traffic citations that BYU administers to students that alledgedly violate its parking and traffic code.

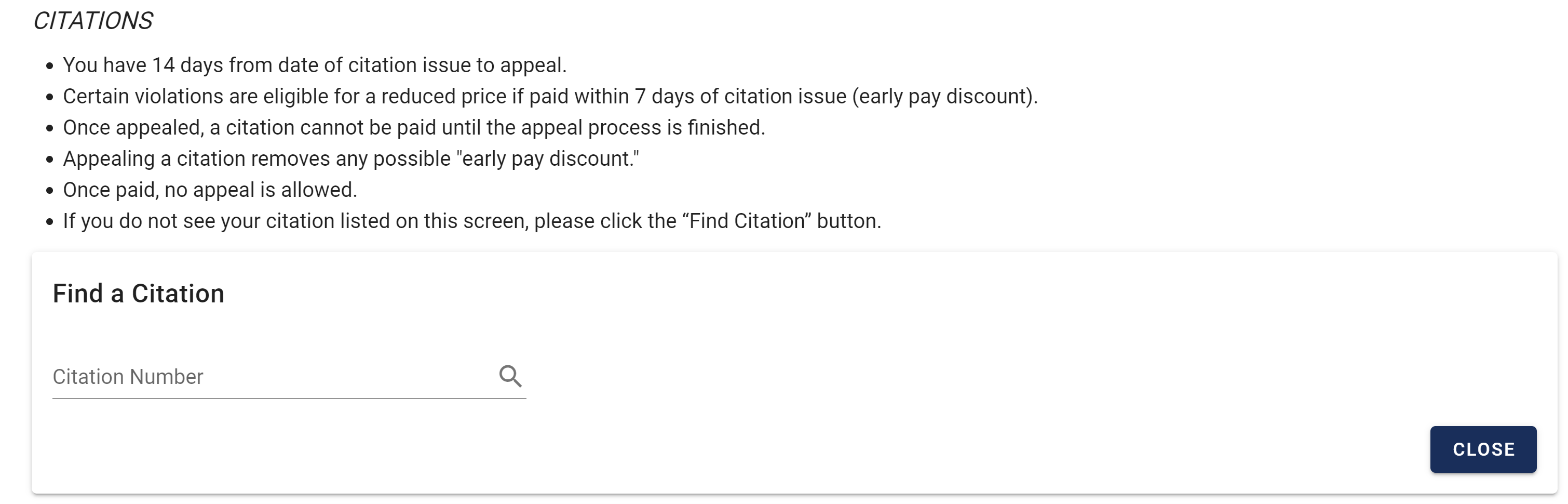

BYU allows anyone with BYU credentials to access any BYU citation through its citation portal availble at this link: https://cars.byu.edu/citations. This tutorial is geared towards BYU students to follow along which is why I chose to use this example; however, all principles and applications discussed in this tutorial can be applied elsewhere, to similar sites that embed their data through a portal.

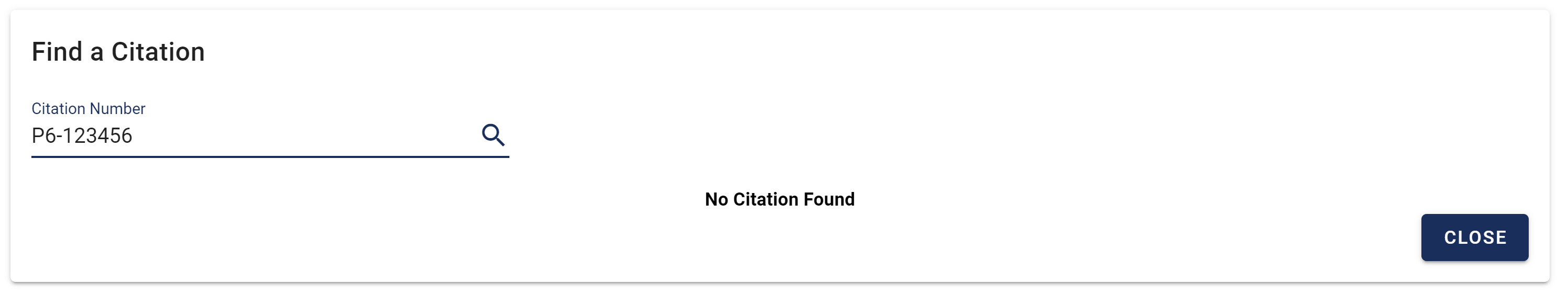

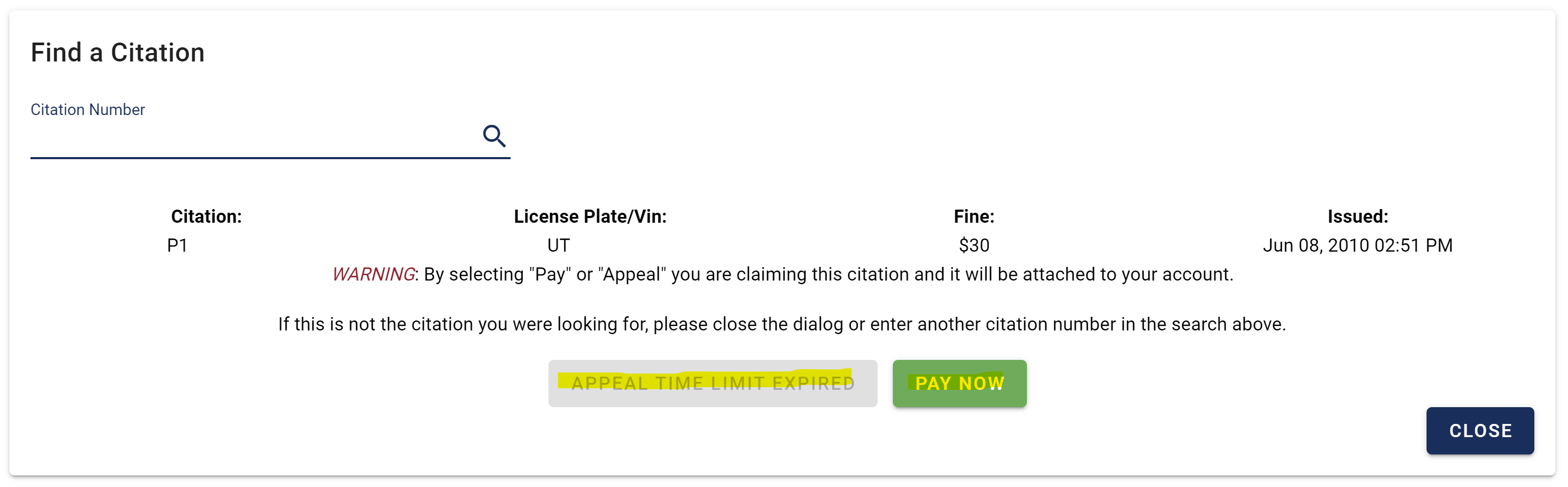

Our script will be entering citation number combinations into this field and scraping the data if the query yields anything.

Here is an example:

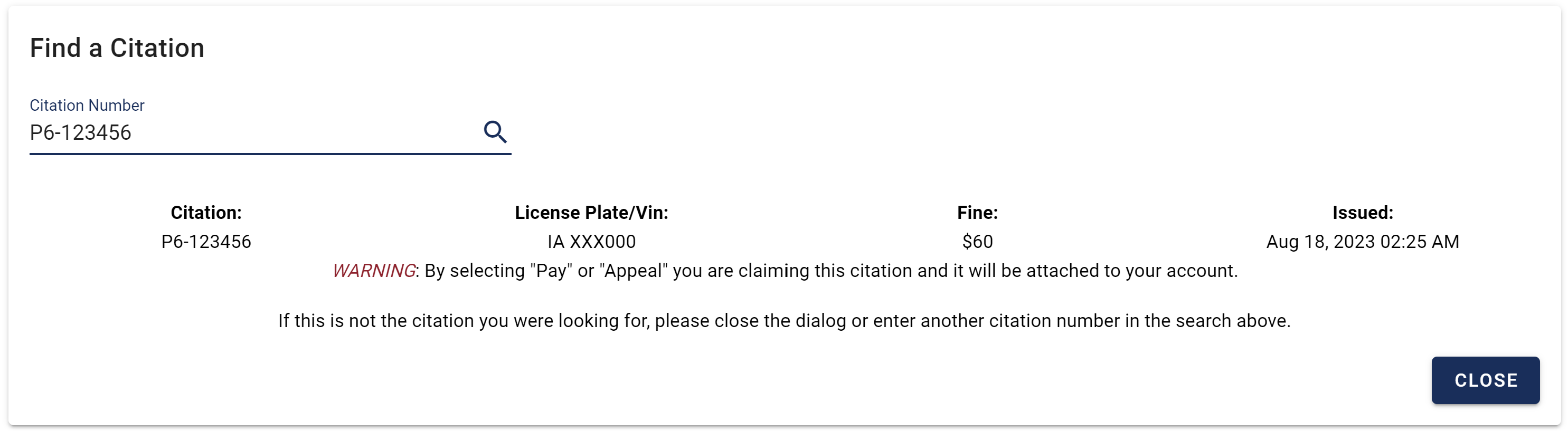

This is a citation that I received in August, though the License Plate number and citation number have been modified for privacy purposes. That is my actual fine though!

We will be able to scrape actual license plate numbers, but we won’t be able to link any identities with these records alone.

Approaching the Problem

When I say we need to define the parameters of the problem, we need to map out how we are going to create this program.

- We need a script that can loop through all possible combinations of citation numbers in order extract the entire listed data base of traffic citations.

- Once a query yields (or doesn’t yield–we need to check for this) information, we need to parse the newly appeared HTML data and format it appropriately (this is the actual data scraping process). This often involves some data cleaning, inevitably.

- We need a way to efficiently store the data that we are parsing so the data doesn’t get lost from one query to the next. Saving data to an external database or file after each scrape (which may be okay for smaller sized tasks like this one) often take up a lot of unnecessary CPU; we can reduce the number of times our program has to do this.

- Error catching. We need our program to handle edge cases. Sometimes a citation might not yield any data. Or sometimes the data might be incomplete. Our scraper needs to be able to handle these issues with ease. Typically when want to scrape data, we want to run our scraper and then come back to it within a day (or sometimes longer!) after it has finished scraping all the data. Our program needs to be reliable. Advanced topics in webscraping include running parallel instances of our scraper, to reduce the total runtime. I won’t get into that in this tutorial.

Creating the Scaper() Class

In this tutorial, I will be using object-orient programming (OOP). I found that this is the most efficient way to organize code for webscraping (and just coding in Python in general). This is what Python excels best at.

For this tutorial I will also be using the following libraries:

import pandas as pd

import threading

import time

import re

import os

We will first create a Scraper class that will essentially be the robot to our program. It will be able to keep track of where we are in the program and it will contain the methods and properties needed to actually scrape the data.

class Scraper():

def __init__(self, url):

#Define the url to scrape

self._url = url

#Define parameters of loop

self.officers = range(1, 10+1)

self.index = range(1, 99999+1)

Our Scraper class will take a url as an argument and we will pass in https://cars.byu.edu/citations to it.

In order to be able to loop through every possible combination of citation number, we have created indexes for officers (1-10) and all possible five-digit combinations (excluding 00000). This will all depend on your problem of interest, for us we need to create citation numbers that look like P#-#####. Through some trial and error, I have determined that the first number (for now) can only be a number (1-10)–this could be this officer number, if my suspicions are correct–and the other five digit #s are interestingly enough in sequential order from the time the citation was given. However, even if the citation numbers weren’t conveniently ordered sequentially, we could still find all possible combinations given that all citations are in that same format.

Loading the Page

def go(self):

driver.get(self._url)

This is a simple method that our Scraper class will have. It will use our globally defined driver object to simply go the url we request it to go to.

We can now update main.py:

if __name__ == "__main__":

driver = selenium_driver()

scraper = Scraper("https://cars.byu.edu/citations/")

scraper.go()

user_input = input("Are you logged in yet? (y/n): ").rstrip().upper()

while user_input != "Y":

print("Waiting for user to log in...")

input("Press any key to continue...")

user_input = input("Are you logged in yet? (y/n): ").rstrip().upper()

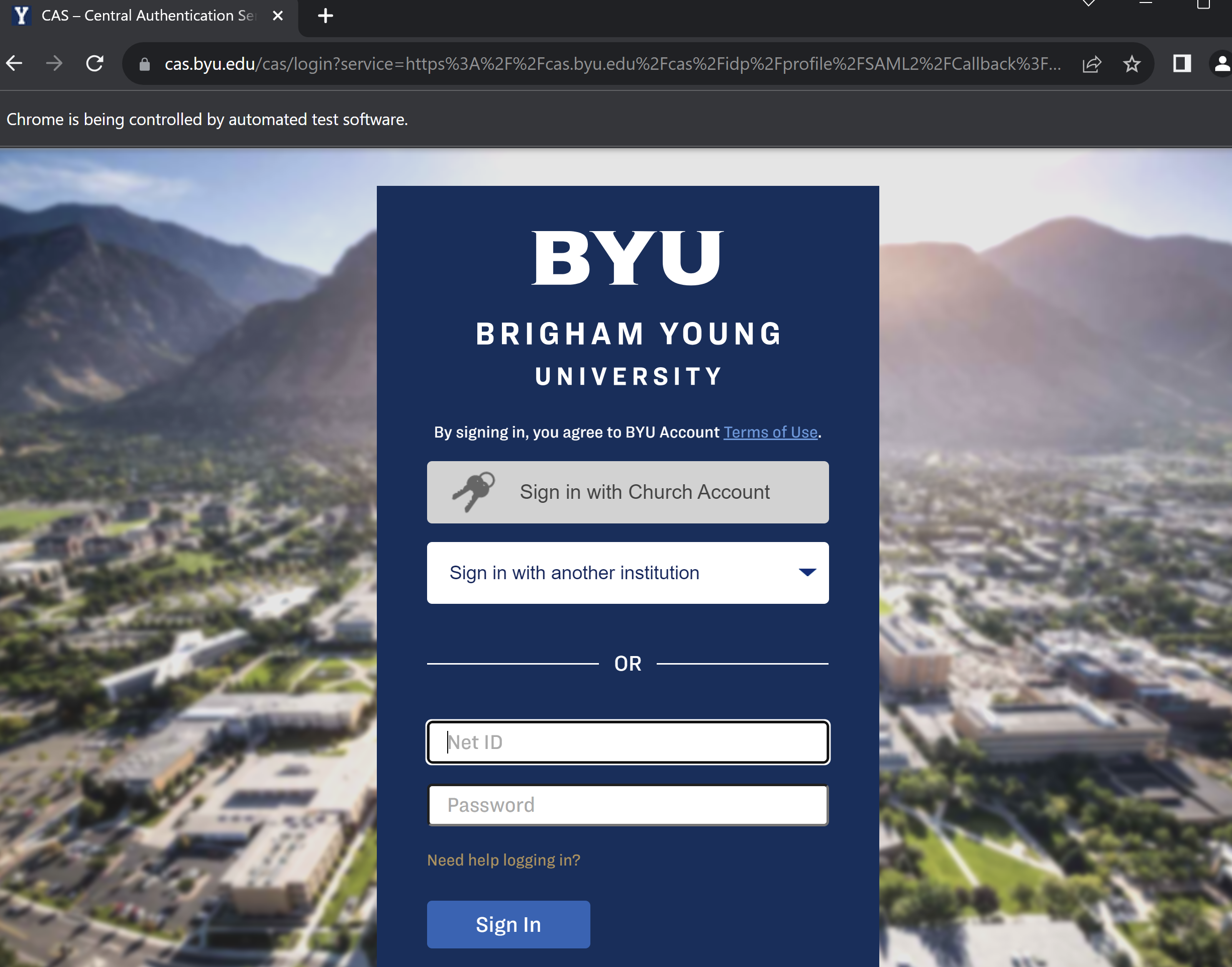

Since https://cars.byu.edu/citations/ requires BYU credentials, we will have manually log in on the first run. This can be automated with APIs, but I won’t get into that in this tutorial.

Another reason why I wanted to use this example is to show you how even sites that require a login can just as easily be scraped–this wouldn’t be possible with traditional static scraping methods.

If you run main.py, (and you’re following along), BYU will ask you to log in:

The Python program will stall on that login page until you tell it (through the input) that you’re logged in. From there, we proceed to access the site like a normal user and send commands to the driver from our Python script.

Defining the Main Loop

Now we are going to directly address #1 in Approaching the Problem. We need to define a loop (or series of loops) that will sequentially or strategically loop through all the possible combinations of citation numbers and insert them into the search bar and proceed with the rest of the program.

Best Practice: Rather than defining a series of recursive functions (unless your program is small or your methods are meant to be ran only a select number of times), it best to define the main sequence of your program using a series of loops to collect the data. Not only is the most efficient, this will save you from recursion errors and help you organize your code more.

When we initially load the page we will need to identify the search bar before we can actually send information. Here is our first taste of using Selenium to interact with the website:

@staticmethod

def find_citation():

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CLASS_NAME, "v-btn__content"))

)

find_citation_btn = driver.find_elements(By.CLASS_NAME, "v-btn__content")[0]

find_citation_btn.click()

Since Python is a sequential programming language, lines of code will be executed within milliseconds. That means as soon as the page is loaded and we call this function, the search bar might not be “there” if not all the elements on the page have loaded.

Best Practice: The Selenium library has a module called expected_conditions which you may have saw as one of the modules you imported. This allows us to control for certain conditions that we “expect” (hence the name) to occur before we proceed with our code. If you want to make sure an element or series of elements are interactable, I found that waiting until the element is clickable (as I have demonstrated) is a very reliable expected condition to wait for before trying to interact with it.

Once we find the element we can go ahead and find the first element that has that class name and click it.

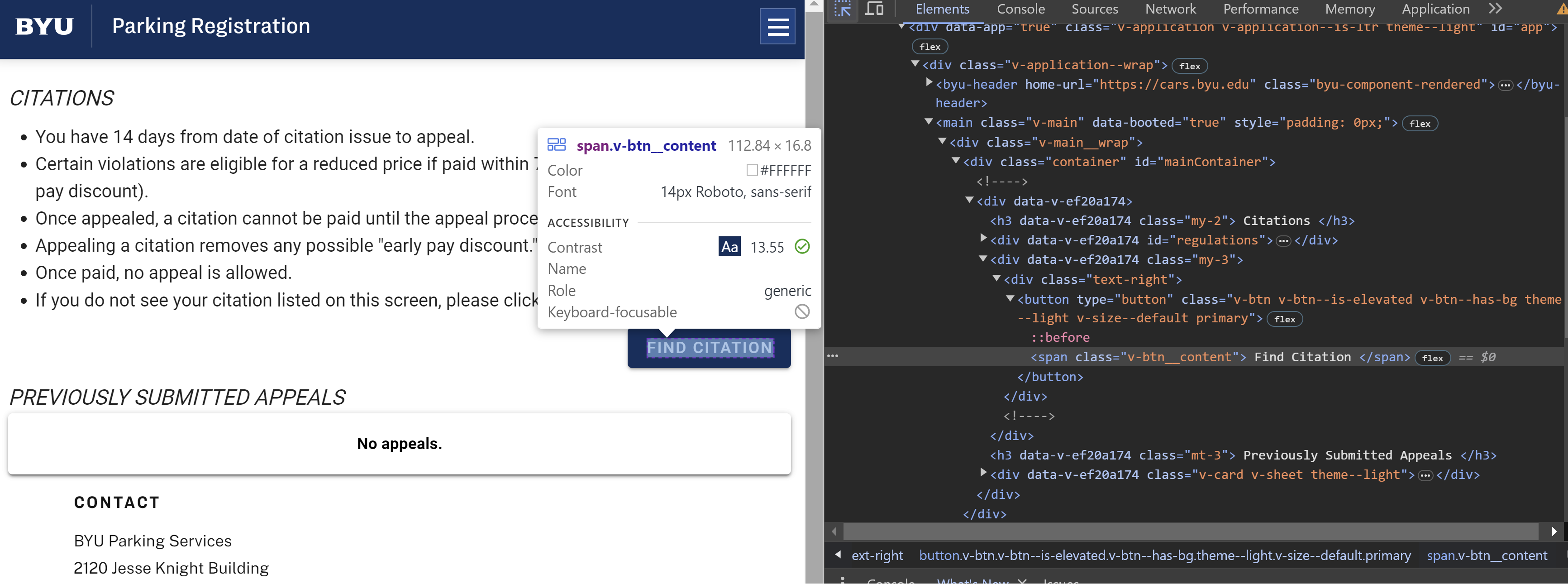

How did I know that was the correct element?

Simply put, I inspected the DOM (ctrl+shift+j on Chrome) and used the interactive tool to see where the “Find Citation” was. It looks like it was consistently listed under the v-btn__content class (classes are denoted with a ‘.’).

We will define the main_loop method inside the Scraper class:

def main_loop(self):

self.go()

self.find_citation()

for i in self.officers:

j = 0

while j < len(self.index):

j += 1

print("Finished scraping all the data.")

This will ensure that all possible combinations are scraped through. I will exmplain in a bit why I chose to use a while loop and manually increase the jth index as opposed to a for loop here in a bit, but essentially it will come in handy if we ever want to “go back in time” to another or different index.

We can call the main_loop() from main.py:

if __name__ == "__main__":

driver = selenium_driver()

scraper = Scraper("https://cars.byu.edu/citations/")

scraper.go()

user_input = input("Are you logged in yet? (y/n): ").rstrip().upper()

while user_input != "Y":

print("Waiting for user to log in...")

input("Press any key to continue...")

user_input = input("Are you logged in yet? (y/n): ").rstrip().upper()

scraper.main_loop()

Great! Now our scraper can click a button, but it can’t do much else.

Send Keys to the Search Bar

We now need to send information to the search bar and see if the query returns any information.

We will define a send_keys() method like this:

@staticmethod

def send_keys(data={"officer": 1, "index": 0}):

index = "0"*(5-len(str(data["index"])))+str(data["index"])

key = f"P{data['officer']}-{index}"

#print(key)

#Search the key into the search bar

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-text-field__slot input"))

)

input_field = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-text-field__slot input")[0]

driver.execute_script("arguments[0].value = '';", input_field)

input_field.send_keys(key)

#Search the citation

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-input__append-inner button"))

)

search_btn = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-input__append-inner button")[0]

search_btn.click()

Sometimes dynamically loaded websites will spoof the identifiers of their web elements. This makes it harder to consistently identify.

One solution is to use an XPATH identifier as opposed to a CSS identifier. Another solution is to find the unique combination of nested HTML tags and target that. This is what I do here.

For example: if I know the link I want to target is always the first link in the p tags of every div that can be identified with a positional or classical identifier, then I can identify the <a> tag even if the <a> isn’t explicitly identifiable through other identifiers.

Here’s code a little broken down:

- Formats the ith and jth index into a citation number

P#-#####. - Waits for the search bar to be identifiable, finds it, clears it if there’s any existing text in it, and then sends the citation number (key) to the search bar. On a side note

driver.execute_script()is literally executing JS code in the browser, which is what I think is one of the neatest things about Selenium. - Waits for the search button to be clickable before interacting with it and then clicks it.

In all honesty, the hardest part about this code is understanding the CSS selectors, which deserves another post on its own.

Best Practice: The best way to find the elements you’re looking for is to actually go into the browser and sift through the HTML yourself. Test out this JavaScript code: document.querySelectorAll(".v-input__append-inner button") (for example) to see if what you think identifies the element actually does. What will identify the element in JS will also identy the element in Selenium using a CSS selector. I also recommend using the debug mode on VSCode and try running driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-input__append-inner button")[0] in the debug console (for example) by putting a breakpoint at that line and seeing if your CSS selector (or other identifier) is what’s causing the problem.

Scraping the Data

This is the bulkiest part of the script. This is the part that will actually take the information that the query returned and parse it own into comprehendable information.

The biggest difficulty with this task is dealing with cases where no data is returned. It’d be great if every citation returned data. But we need to test for this.

These are our functions:

def get_data(self):

citation_data = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .col")

no_data_text = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .text-center h4")

while not and len(citation_data) < 1 and len(no_data_text) < 1:

citation_data = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .col")

no_data_text = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .text-center h4")

time.sleep(0.1)

if len(no_data_text) >= 1:

return pd.DataFrame()

else:

#Now we need to parse the data into a pandas data frame

#Additional information about the citation if it exists and whether or not they paid the ticket

additionalInfo = self.checkPayment()

return pd.concat([self.format_text([el.text for el in citation_data]), additionalInfo], axis=1)

@staticmethod

def format_text(text_arr):

#Takes the text data and returns a formatted pandas frame

cols = [x.split(":")[0] for x in text_arr]

data = [x.split(":", 1)[1].strip() if ":" in x else x.strip() for x in text_arr]

row = pd.DataFrame(data, cols).transpose()

return row

This is essentially the error we are trying to digest. Instead of using Selenium’s expected_conditions module, we create our own wait time method with a while loop. The logic works like this:

- Check to see if the citation data has loaded (data to be found in

.v-card__text .col). If nothing is returned, it either is still loading or there is no data to be found for that citation. - Check to see if the header tag that holds the text “No Citation Found” has been identified (as it would appear in the picture above). Similarly, if there is nothing returned, it either hasn’t been loaded yet, or there actually is data for the citation.

- Only one of those selectors has to return data for the program to proceed. I don’t use

expected_conditionsbecause the loop I’m currently running is simply faster. If ran a wait on either thecitation_dataorno_data_textI would have to set a fixed amount of time for the data to appear (or for “No Citation Found”) to appear and even then, it wouldn’t guarantee for either of those variables to contain data. Using this method guaruntees that one of those will contain data. It does warn that the loop could take forever if the Selenium driver encounters an error such that neither of the conditions we check for become false. We will solve for this shortly hereafter. - If there is data, we simply get the text in all the columns (formatted in an array) and pass it into our

format_textmethod that returns a nicely formatted pandas table. This is what we want. This is essentially the inputs to outputs of any scraper.

Applied Example:

[el.text for el in citation_data]

-> ['Citation:\nP1-00000', 'License Plate/Vin:\nUT XXX123', 'Fine:\n$20', 'Issued:\nJun 01, 2010 01:28 PM']

#In self.format_text(text_arr) method

[x.split(":")[0] for x in text_arr]

-> ['Citation', 'License Plate/Vin', 'Fine', 'Issued']

[x.split(":", 1)[1].strip() if ":" in x else x.strip() for x in text_arr]

-> ['P1-00000', 'UT XXX123', '$20', 'Jun 01, 2010 01:28 PM']

row = pd.DataFrame(data, cols).transpose()

-> Citation License Plate/Vin Fine Issued

0 P1-00000 UT XXX123 $20 Jun 01, 2010 01:28 PM

Here is another function that scrapes additional information (used in the get_data() method):

@staticmethod

def checkPayment():

#Check to see if the payment is available

#We can assume that the buttons to appeal and pay have loaded when the citation has loaded so we don't need to load again

buttons = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .text-center button")

citationInfo = {"CitationText": None,

"Unpaid": False}

if len(buttons) > 0:

if len(buttons) > 1:

citationInfo = {"CitationText": buttons[0].text,

"Unpaid": True}

elif len(buttons) == 0:

#We have to determine what kind of information is left to be scraped

if "APPEAL" in buttons[0].text.upper():

citationInfo = {"CitationText": buttons[0].text,

"Unpaid": False}

elif "PAY" in buttons[0].text.upper():

citationInfo = {"CitationText": None,

"Unpaid": True}

#Two columns to be merged with the row that scrapes the general information

return pd.DataFrame.from_dict(citationInfo, orient='index').T

I won’t dissect the logic of the checkPayment() function too much (this function is completely optional, it just adds more information to our data frame), but essentially it is checking to see if the citation is payable and it is parsing the text of the citation button. This is just additional information that can be merged with the rest of the information.

Now we can update our main_loop function:

def main_loop(self):

self.go()

self.find_citation()

for i in self.officers:

j = 0

while j < len(self.index):

self.send_keys({"officer": i, "index": j})

#Store the data in the RAM

#Save it to a file when it is the last index

scraped_data = self.get_data()

self._citation_loaded = True

j += 1

In our updates we:

- Sent keys to the search bar and ran the query with the current ith and jth index.

- Scraped the data (if there was any)

Now that we scraped the data we need to efficiently store the data.

Storing & Saving the Scraped Data

In this stage of the process we will need to transfer the scraped data after each iteration to some other place. We could store it in an external file, and we will eventually do this, however, performing external file operations every single iteration is costly from a computer resource perspective. We can make the code more efficient by only saving the data to an external file only when we have to. Until that time, we can save the scraped data to a place in the RAM (temporary memory).

We will initialize a global data frame called DATA. Through this variable we will store all appendages of our scraped data.

We will create a function called save_data() that can be called from the main_loop(). This function will be in charge of adding the scraped data to the DATA as well as saving the data set to an external file when save = True.

Optional: Additionally, before I save the data set to the external file, I perform some pandas operations on the data set to clean it up a bit:

- I extract the officer number from the citation number

- I convert the “Fine” column into numerical data

- I convert the date column into two separate date columns: one that stores the day of the year, and the other that stores the time of day that the citation was given.

One important thing to note here is the way I save the pandas data frame to the csv file: For efficiency purposes, it is better to append the data to any existing data (as opposed to just overwriting the file each time).

I also overwrite the DATA variable (by setting it equal to an empty data frame–pd.DataFrame()) after each time I save it to the file. This is another way to improve efficiency if you are scraping a potentially large data set–that way Python won’t waste computer resources by concatenating data to a potentially large DATA variable that’s already saved to an external data file.

DATA = pd.DataFrame()

def save_data(data, save=False):

global DATA

#Don't add empty data

if not data.empty and not data.iloc[-1][['Citation', 'License Plate/Vin', 'Fine', 'Issued', 'CitationText']].isna().all():

if DATA.empty:

DATA = data

else:

DATA = pd.concat([DATA, data]).reset_index(drop=True)

if save:

#Clean the data before saving it to the file

DATA["Officer"] = DATA["Citation"].apply(lambda x: re.search(r'P(\d+)', str(x)).group(1) if isinstance(x, str) and re.search(r'P(\d+)', str(x)) else None)

DATA["Fine"] = DATA["Fine"].apply(lambda x: float(x.replace('$', '').replace(',', '')) if isinstance(x, str) else x)

DATA["Residence"] = DATA["License Plate/Vin"].str.split().str[0]

DATA["IssuedDate"] = pd.to_datetime(DATA["Issued"], format='%b %d, %Y %I:%M %p').dt.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

DATA["IssuedTime"] = pd.to_datetime(DATA["Issued"], format='%b %d, %Y %I:%M %p').dt.strftime('%I:%M %p')

if os.path.exists("ParkingCitations.csv"):

DATA.to_csv("ParkingCitations.csv", mode='a', index=False, header=False)

else:

DATA.to_csv("ParkingCitations.csv", index=False)

DATA = pd.DataFrame()

We will then save the DATA periodically. This can be done really whenever, but I decided a good time to save the data frame is after every 1000 scrapes.

Thus we can modify the main_loop() like this:

def main_loop(self):

self.go()

self.find_citation()

for i in self.officers:

j = 0

while j < len(self.index):

self.send_keys({"officer": i, "index": j})

#Store the data in the RAM

#Save it to a file when it is the last index

#i.e. save it to a file when we are done scraping each officer's citations

scraped_data = self.get_data()

if not scraped_data.empty:

#Save to a file every 1000 rows scraped, or if it's the last index

to_file = (j == len(self.index)-1) or j % 1000 == 0

save_data(scraped_data, save = to_file)

else:

print("No data")

#Display to the console the most recent data scraped

print("Most recent data scraped:")

print(DATA.tail(5))

j += 1

I added some diagnostic information in there as well to show the five most recently scraped citations after each iteration.

Checking for No Data Revisted: Threads

We will now return to the potential issue that occurred in get_data(). Earlier when we created a customized wait method using a while loop that essentially waited until either “No Citation Found” or until actual data was found we discovered that this while loop could possibly wait forever.

Solution: We can create an asynchronous timer that will run outside of Scraper(). This timer will essentially given us a threshold to say whether the data is taking too long to load. If the data is taking too long to load we can signal back to the scraper object to try and query up the query again–sometimes this is a Selenium error. Threads allow us to control for these abnormal stops in the driver.

Here is the function that we will run using the threading library:

def measure_time(start_time, s, threshold=10.1):

counting = True

while counting and not s.citation_loaded:

current = time.perf_counter() - start_time

if current >= threshold:

counting = False

s.flag = True

s.go()

time.sleep(0.1)

This function starts counting until 10 once it is called. If the thread is not stopped before the 10 seconds is up, then it will signal back to the scraper object (argument s–that’s the benefit of OOP, that we can refer back to the same object even when it’s passed through a function) that the scraper failed to query up data (or no data) within an adequate period of time (10 seconds in our case). I reload the page with s.go() to prevent the driver from freezing up.

NOTE: time.sleep(0.1) is there to conserve computer resources; the timer will only update every 100 ms.

I refer to some properties of Scraper() in measure_time that I haven’t quite yet defined, so let’s do that:

class Scraper():

def __init__(self, url):

#Define the url to scrape

self._url = url

#Some properties that will help us see if the citation has been found

self._citation_loaded = False

self._flag = False

#Define parameters of loop

self.officers = range(1, 10+1)

self.index = range(1, 99999+1)

Now some getters and setters that can be referenced from measure_time

@property

def citation_loaded(self):

return self._citation_loaded

@property

def flag(self):

return self._flag

@flag.setter

def flag(self, change):

self._flag = change

Thus, if measure time triggers the flag property of the scraper, we need the while loop to stop.

Implementing the Thread in our Scraping Methods

We can easily modify the get_data() method by including self.flag as a conditional in the while loop.

Now that the structure and logic of measure_time is established in Scraper(), we need to actually create the thread in our scraping methods.

First, we modify the get_data() method. Essentially, we start the asynchronous timer before any “problematic” code chunks start–i.e. before the while loop prohibits the Selenium driver from freezing up. If the scrape is successful, we can join() (stop) the thread before the timer is up and proceed with the scraping.

def get_data(self):

#Time how long it takes to scrape each citation

start_time = time.perf_counter()

self._citation_loaded = False

# Create and start the thread for measuring time

time_thread = threading.Thread(target=measure_time, args=(start_time,self))

time_thread.start()

citation_data = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .col")

no_data_text = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .text-center h4")

while not self.flag and len(citation_data) < 1 and len(no_data_text) < 1:

citation_data = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .col")

no_data_text = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-card__text .text-center h4")

time.sleep(0.1)

self._citation_loaded = True

#Join the current thread

time_thread.join()

if len(no_data_text) >= 1:

return pd.DataFrame()

else:

#Now we need to parse the data into a pandas data frame

#Additional information about the citation if it exists and whether or not they paid the ticket

additionalInfo = self.checkPayment()

return pd.concat([self.format_text([el.text for el in citation_data]), additionalInfo], axis=1)

Best Practice: Over large iterations with Selenium (as we are doing here), Selenium has a tendency to freeze up in response to the lag time between the actions from the script and the responses from the server. As a result, it’s best to prevent these freezes by implementing these threads over every scraping method–areas where Selenium is susceptible to these lags/timeout errors.

Thus, we will also implement our measure_time() thread over our send_keys() method (since it interacts directly with Selenium).

Here’s how we can modify the function (similar to how we implemented the thread with get_data()).

def send_keys(self, data={"officer": 1, "index": 0}):

self._citation_loaded = False

index = "0"*(5-len(str(data["index"])))+str(data["index"])

key = f"P{data['officer']}-{index}"

#print(key)

#Time how long it takes to load each citation

start_time = time.perf_counter()

# Create and start the thread for measuring time

time_thread = threading.Thread(target=measure_time, args=(start_time,self))

time_thread.start()

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-text-field__slot input"))

)

input_field = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-text-field__slot input")[0]

driver.execute_script("arguments[0].value = '';", input_field)

input_field.send_keys(key)

#Search the citation

WebDriverWait(driver, 10).until(

EC.element_to_be_clickable((By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-input__append-inner button"))

)

search_btn = driver.find_elements(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".v-input__append-inner button")[0]

search_btn.click()

self._citation_loaded = True

time_thread.join()

This is essentially the same code as before but we are surrounding the code that interacts with the driver with our thread implementation (same as in get_data()). We also need to change it into a dynamic function by adding self to the function parameters so we can set self._citation_loaded = False at the beginning of the method and True once the keys have been sent.

Modifying the main_loop()

We also need to update the main_loop to retry the citation in the case that one of our scraping methods ended in an error or caused our thread to time out:

def main_loop(self):

self.go()

self.find_citation()

for i in self.officers:

j = 0

while j < len(self.index):

#Reset the flag:

if self._flag == True:

self._flag = False

self.go()

self.find_citation()

try:

self.send_keys({"officer": i, "index": j})

#Store the data in the RAM

#Save it to a file when it is the last index

#i.e. save it to a file when we are done scraping each officer's citations

scraped_data = self.get_data()

if not scraped_data.empty:

#Save to a file every 1000 rows scraped, or if it's the last index

to_file = (j == len(self.index)-1) or j % 1000 == 0

save_data(scraped_data, save = to_file)

else:

print("No data")

except Exception as e:

now = datetime.datetime.now()

index = "0"*(5-len(str(j)))+str(j)

key = f"P{i}-{index}"

error_message = f"{now}: {str(e)};\nThere was an error sending the keys or scraping the data: {key}"

with open("errors.txt", "a") as f:

f.write(error_message + "\n\n")

self._flag = True

if self._flag:

#This property can only be set true by the measure_time thread

j -= 1

#Generally increase the jth index after each iteration

j += 1

print("Finished scraping all the data.")

Here’s the updates that occurred:

- If

flagis true (meaning that the timer finished before the data could load or be scraped), we need to first and foremost reset theflagproperty to false so it can be ready for the next iteration, but then secondly, we can repeat the citation number again to get another attempt at scraping the data. - Put some error catching around our scraping methods. In case anything goes wrong–perhaps something that we didn’t intend in the driver or a timeout exception–we can log that to the errors.txt file and try again and see exactly where the error occurred.

- If the flag is true, go back to the previous citation and try again.

Conclusion

The scraper is complete and ready to be ran. I hope this was helpful for those of you who followed along. I hope you learned some guiding principles as you venture on to go on to build your own sraping projects. This is a basic model that certainly worked for the project that I was working on, but the truth is every website is built different and you will have to learn how to adjust to their unique style and dynamics. Again, all the code is posted on my Github here.

Optional Diagnostic Information

When I am running my scrapers, especially scrapers that run for hours on end, I typically like to time to see how long it’s been running.

Here’s some code to time the scraper and output that diagnostic information for every 10 iterations:

Add the following line of code to the __init__() function in the Scraper():

#Starting time

self.start_time = time.perf_counter()

(Within the Scraper() class)

def calculateTime(self):

self.end_time = time.perf_counter()

total_seconds = self.end_time - self.start_time

hours = total_seconds // 3600

remaining_seconds = total_seconds % 3600

minutes = remaining_seconds // 60

seconds = remaining_seconds % 60

print(f"\nTotal seconds elapsed: {total_seconds:.4f}")

print(f"That's {hours} hours, {minutes} minutes, and {seconds:.4f} seconds.\n")

return total_seconds

Within the main_loop:

if j % 10 == 0:

self.calculateTime()

The current version of my scraper on GitHub also has methodology to start at a specific citation in the database. This involves changing the outisde for loop in the main_loop to a while loop.

I also have support that ends scraping the current “Officer” # if the scraper runs into 50 consecutive citations with no data and the previous citation scraped was within a month of being issued–this prevents the scraper going to 99999 for every ith iteration.

Additional Resources

A multi-part tutorial that I have watched and would recommend:

A more wholistic approach and walkthrough to Selenium:

The documentation for Selenium, specifically for locating elements in the DOM which I didn’t go over in depth: