Introduction

The popular Korean game called “The Name Compatibility Test” (이름궁합 테스트) is a game which takes two (Korean) names and returns a compatibility score 0-100, representing a percentage. I was curious to see if some names were naturally more “compatible” than others. To investigate this I created this research project. I wanted to figure out if I could come up with a method to identify which names are more compatible than others.

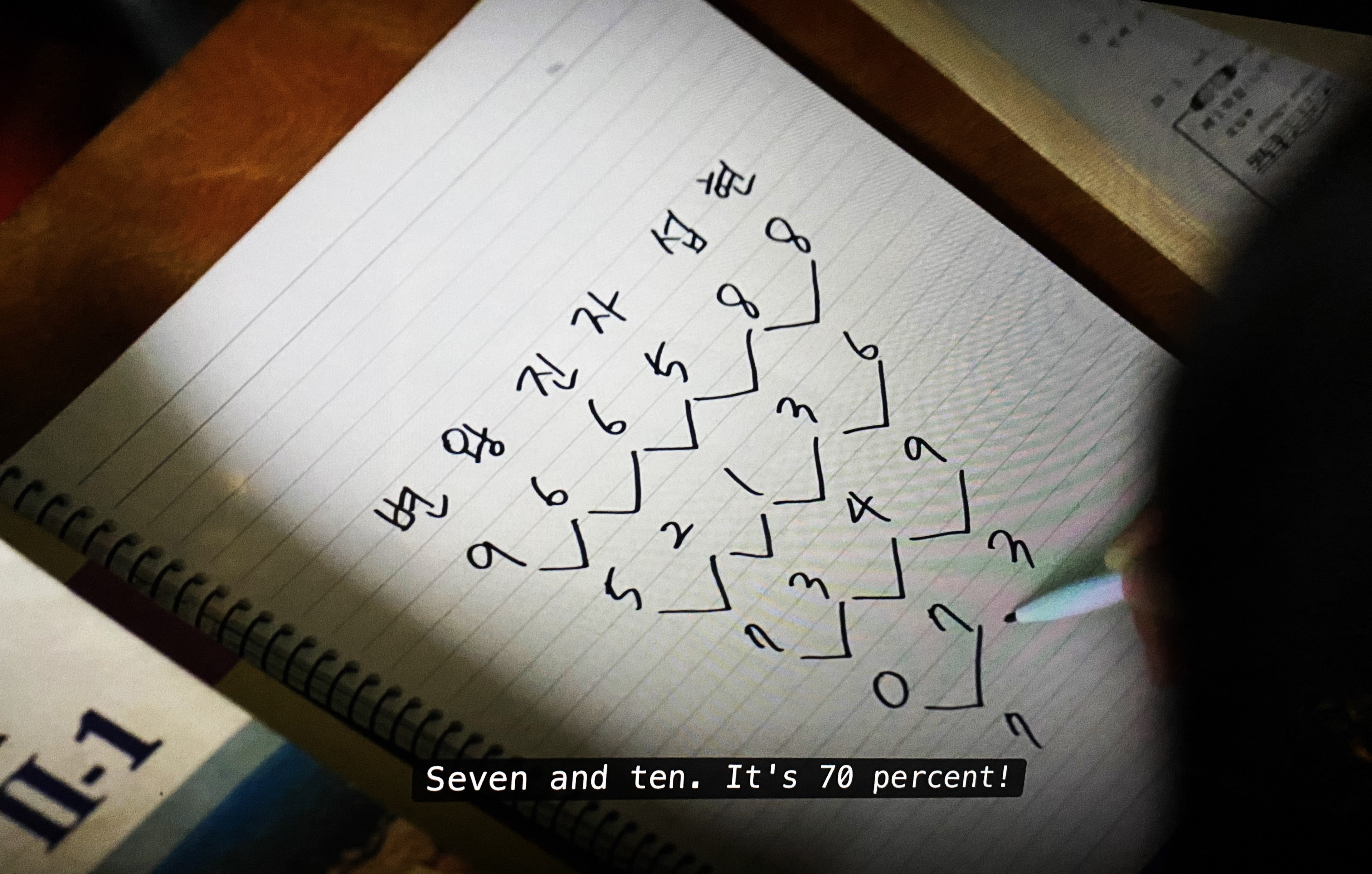

Though the game has a few known popular variations. For the intents of this of study I will be using the version of the game as seen in the K-drama, Reply 1988.

Here’s how the game works:

- Interweave two (Korean) names, with the guy name going first

- Compute the number of total strokes it takes to write each syllable and write it on the line directly beneath

- Compute sliding sums of the resulting array of numbers to proceed to the next line. If the sum $\geq$ 10, then you must subtract 10 to keep the resulting number between 0-9.

- Repeat this process until you end up with a final number 0-100. This is the compatibility score representing a “percentage” of how compatible these two names are.

This process is illustrated on this project’s dashboard here: https://namecompatibility.streamlit.app/

Using this framework, will attempt to answer the following research questions:

- What names have statistically better odds at yielding higher compatibility scores?

- What is it about certain names that yield high compatibility scores?

The content for this project is located on my Github at https://github.com/SamLeeBYU/NameCompatibility.

The Data

To answer the research questions of interest I needed to obtain a dataset of plausible names to draw from for both males and females. Ideally, census data would be most appropriate for this. However, I was unable to feasibly obtain a dataset that consisted of population values for Korean names. Sources I was able to locate failed to cite their sources of data. Alteratively I could pool in all of these data sets and create a larger sample of names. However, for the purposes of this study, pleading practicality on my end, I will use a sample data set of the most popular male and female Korean names as cited by Wikipedia. Additionally, I will use Wikipedia’s compilation of Korean surnames here. See the data compiled from these sources compiled in Data/popular_names.csv and Data/surnames.csv on this project’s Github repository.

Using the sample from popular_names.csv, for each name in the sample, we will first create a vector of every possible combination of first name and last name for both male and female-based names. Using these vectors, we will create a distribution for each name by running the compatibility test for each name in each sex-based vector with each name in the opposite sex-based vector. Within the sample I have collected, this means that for each of the 34,720 male names, each of these names will have to be tested (through the compatibility test) against the equivalent 34,720 female names.

Creating Aliases

Given the necessity of an $n\times n$ algorithm (34720 $\times$ 34720), I came up with an idea to reduce the computations needed to compute these distributions using aliases. The key in this strategy comes from recognizing that each name does not have a unique character stroke distribution. I found all of the unique character stroke distributions and assigned all of the names that have the same character stroke distributions under a single “alias”. The name that is designated as the alias is the first name that appears in the vector of names with a unique character stroke distribution.

This chunk of code creates the stroke distributions for each name in both the male-based and female-based name vectors (this code simultaneously creates all the 34,720 name combinations for male and female names):

male_stroke_distributions = []

male_names = []

male_subset = popular_names[popular_names["성"] == "남"]

female_stroke_distributions = []

female_names = []

female_subset = popular_names[popular_names["성"] == "여"]

for i, name in male_subset.iterrows():

for k, surname_k in surnames.iterrows():

full_name = f'{surname_k["성"]}{name["이름"]}'

male_names.append(full_name)

decomposition = [map_strokes(char, i) for i, char in enumerate(decompose(full_name))]

male_stroke_distributions.append([sum(decomposition[i:i+3]) for i in range(0, len(decomposition)-2, 3)])

for i, name in female_subset.iterrows():

for k, surname_k in surnames.iterrows():

full_name = f'{surname_k["성"]}{name["이름"]}'

female_names.append(full_name)

decomposition = [map_strokes(char, i) for i, char in enumerate(decompose(full_name))]

female_stroke_distributions.append([sum(decomposition[i:i+3]) for i in range(0, len(decomposition)-2, 3)])

After creating the names we then assign each of the names into an alias:

male_unique_stroke_distributions = []

male_aliases = {}

for i in range(len(male_stroke_distributions)):

x = male_stroke_distributions[i]

unique = True

for j in range(len(male_unique_stroke_distributions)):

distribution = male_unique_stroke_distributions[j]

if x == distribution:

unique = False

male_aliases[list(male_aliases.keys())[j]].append(male_names[i])

if unique:

male_aliases[male_names[i]] = [male_names[i]]

male_unique_stroke_distributions.append(x)

female_unique_stroke_distributions = []

female_aliases = {}

for i in range(len(female_stroke_distributions)):

x = female_stroke_distributions[i]

unique = True

for j in range(len(female_unique_stroke_distributions)):

distribution = female_unique_stroke_distributions[j]

if x == distribution:

unique = False

female_aliases[list(female_aliases.keys())[j]].append(female_names[i])

if unique:

female_aliases[female_names[i]] = [female_names[i]]

female_unique_stroke_distributions.append(x)

for name, alias in male_aliases.items():

male_aliases[name] = np.unique(alias).tolist()

for name, alias in female_aliases.items():

female_aliases[name] = np.unique(alias).tolist()

This code creates a python dictionary of all the aliases for both the female and male-based names. All the aliases and all the names associated under each alias can be found in Data/aliases.json.

Now that we have created a set of aliases, we can run computations on these aliases, knowing that they represent the vector of names under each alias, instead of running computations on each single name, quadratically increasing the efficiency of my algorithms used in this project. The code above resulted in 575 female aliases and 775 male aliases.

The aliases can be further explored on the project’s dashboard.

Distributional Hierarchies

I calculated distributions–distributions of the compatibility scores–for each male and female alias and assigned these distributions into a distributional matrix. The the goal is to use these distributions to calculate which names (or equivalently, which alias), statistically yields higher compatibility scores. Which distribution is the “best”? How can we determine that?

If these distributions followed some known distribution, then it would be reasonable to compute maximum likelihood estimators for each distribution and create a hierarchy (a ranking system) based on these maximum likelihood estimators to answer this research question. However, computing such maximum likelihood estimators are not practical for the purpose of this project. Instead, in this analysis, I will show how we can create distributional hierarchies using a process of monte carlo estimation.

To do this, I created probability matrices for both the male and female aliases. These probability matrices consist of the probability that a randomly selected compatibility score from the $i$th alias will be greater than a randomly selected score from the $j$th alias $\forall i\neq j$.

def compare(i, j, sex="male", plot=False):

data_i = distributions[i]

data_j = distributions[j]

def get_column(matrix, i=i):

return [row[i] for row in matrix]

if sex == "male":

name_i = list(male_aliases.keys())[i]

name_j = list(male_aliases.keys())[j]

else:

data_i = get_column(distributions)

data_j = get_column(distributions, i=j)

data = np.array(data_i) - np.array(data_j)

return np.mean(data > 0)

male_probability_matrix = []

female_probability_matrix = []

for i in range(len(male_aliases)):

print(i)

row_i = []

for j in range(len(male_aliases)):

row_i.append(compare(i,j))

male_probability_matrix.append(row_i)

for i in range(len(female_aliases)):

print(i)

row_i = []

for j in range(len(female_aliases)):

row_i.append(compare(i,j,sex="female"))

female_probability_matrix.append(row_i)

We did not need to take another random sample for the monte carlo approximation from $\text{data}_i$ or $\text{data}_j$ because these were already random samples. We wish to estimate how these distributions compare at the same indices: i.e. if the $i$th alias is 가이준 and if the $j$th alias is 기이준, we want to know know how 가이준 scores 김하은 (for example) vs. how 기이준 scores with 김하은. The result is a distribution of Bernoulli random variables ($p_{ij}$) for each $i$th alias. Storing these probability distributions in a matrix, we will use this matrix to compute the hierarchal structure.

To allocate a hierarchal order which certain aliases are statistically more likely to yield higher compatibility scores, I created the following process:

- Start by randomly assigning an initial allocation at rank 0. This allocation consists of pairs of $i$s and $j$s (an odd number of indices in a rank will leave one left over)

- For each pair, referring to the respective probability matrix calculated above, determine if $p_{ij} > 0.5$–NOTE: due to how $p_{ij}$ is calculated, if $p_{ij} \leq 0.5$ then $p_{ji}=1-p_{ij}>0.5$

- If $p_{ij} > 0.5$, then send the $i$th alias up a rank and the $j$th alias down a rank. If an index is left without a pair, it remains on that rank.

- Loop through each rank again repeating steps 2-3 until an equilibrium is obtained. An equilibrium is obtained when there is only a single index (alias) on each rank.

- Repeat steps 1-4 for a given number of iterations as there are many possible equilibria depending on the initial random allocation. Averaging the final ranks as an outcome yields an estimate of the true hierarchal structure of where each alias stands in relation to all other distributions.

What steps 1-4 look like in Python (this code shows how the male hierarchy is computed. The exact same process is done for the female hierarchy):

initial_allocation = list(range(0, len(male_aliases)))

random.shuffle(initial_allocation)

allocation = [(initial_allocation[i], initial_allocation[i + 1]) if i + 1 < len(initial_allocation) else

(initial_allocation[i],) for i in range(0, len(initial_allocation), 2)]

hierarchy = {

0: allocation

}

def is_equilibrium():

equilibrium = True

for level in list(hierarchy.keys()):

decomposition = [n for pair in hierarchy[level] for n in pair]

if len(decomposition) != 1:

equilibrium = False

break

return equilibrium

while not is_equilibrium():

for level in list(hierarchy.keys()):

if not level+1 in hierarchy:

hierarchy[level+1] = []

if not level-1 in hierarchy:

hierarchy[level-1] = []

keep_ns = []

for n in range(len(hierarchy[level])):

pair = hierarchy[level][n]

try:

i = pair[0]

j = pair[1]

if male_probability_matrix[i][j] > 0.5:

hierarchy[level+1].append(i)

hierarchy[level-1].append(j)

else:

hierarchy[level+1].append(j)

hierarchy[level-1].append(i)

except Exception as e:

try:

keep_ns.append(pair[0])

except Exception as e:

keep_ns.append(pair)

hierarchy[level] = keep_ns

for level in list(hierarchy.keys()):

if len(hierarchy[level]) <= 0:

hierarchy.pop(level)

else:

hierarchy[level] = [(hierarchy[level][x], hierarchy[level][x + 1]) if x + 1 < len(hierarchy[level]) else

(hierarchy[level][x],) for x in range(0, len(hierarchy[level]), 2)]

See my dashboard to see the results of the distributional hierarchal computations.

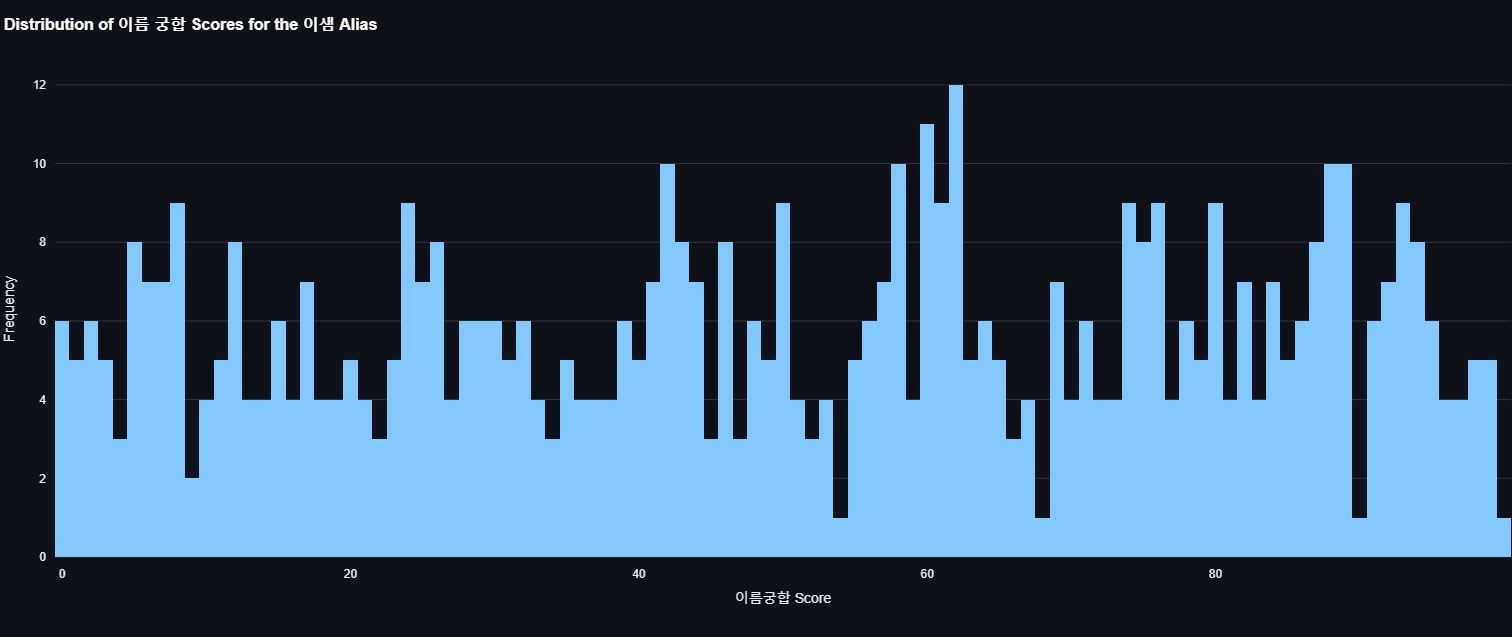

Here is the distribution of compatibility scores of my name.

Conclusion

In this analysis we took combinations of 34,720 potential Korean names and analyzed the distribution of their compatibility scores using the popular Name Compatibility Test framework. We created aliases to simplify computations. We created an algorithm that sorts the sampled distributions into an estimated hierarchal order. A future study would specify how certain our hierarchal order is. We found that the 간영기 male alias and the 간슬기 female alias performed at the top of the hierarchal algorithm. Names under these aliases tend to score higher than other names in our sample.

Limitations

Given the limitations on how the sample was obtained, this analysis does not give insight into how might a distribution (or a compatibility distribution for your own distribution) might compare against the Korean population at large, only simply against the sample I compared it against. The sample only consists of popular names from the 1940s-present, hence, though the results from these insights give insights to how the compatibility distributions compare against each other based on the sample at hand, they are likely biased due to missing data and should not be extrapolated to the Korean population at large. However, with a proper data set, these methods may be applicable in alternative settings.

Additionally the the algorithms to determine the hierarchal order of the compatibility scores of each distribution is optimally efficient. This limited the number of iterations that could be run for the purposes of this project. Furthermore, the variance of each distribution was not considered in the hierarchal algorithm. A future improvement could adjust the algorithm to not only account for whether one distribution is more likely to score higher than another but by how much and with how much certainty.